I’ve always loved comedy, especially the kind that pushes boundaries. As a kid, I didn’t fully understand Richard Pryor’s perspective, but his raw energy and sharp wit captivated me. Later in life, his story took on a deeper meaning because the same disease that stole his gift is the one trying to take mine.

Saturday Night Live was a staple of my childhood. The original cast shaped my sense of humor, and no one fascinated me more than Richard Pryor. His style was aggressive, his language foul, but there was something magnetic about him.

One of my favorite SNL skits is the infamous word association game between Pryor and Chevy Chase. Even today, it remains one of the edgiest moments in television history. After seeing that, I started collecting Pryor’s albums and watching his specials on VHS. He was fearless, willing to say what others wouldn’t.

But MS doesn’t care how fearless you are. Eventually, it took Pryor out of the spotlight. His disease progressed to the point where people could no longer laugh with him. The tragedy of what he had lost was too much for fans.

We tend to admire celebrities with MS when they look like Jack Osbourne or Selma Blair—young, strong, still able to fight. But we forget about those like Annette Funicello, Teri Garr, and Richard Pryor, whose decline reminded us too much of our own mortality.

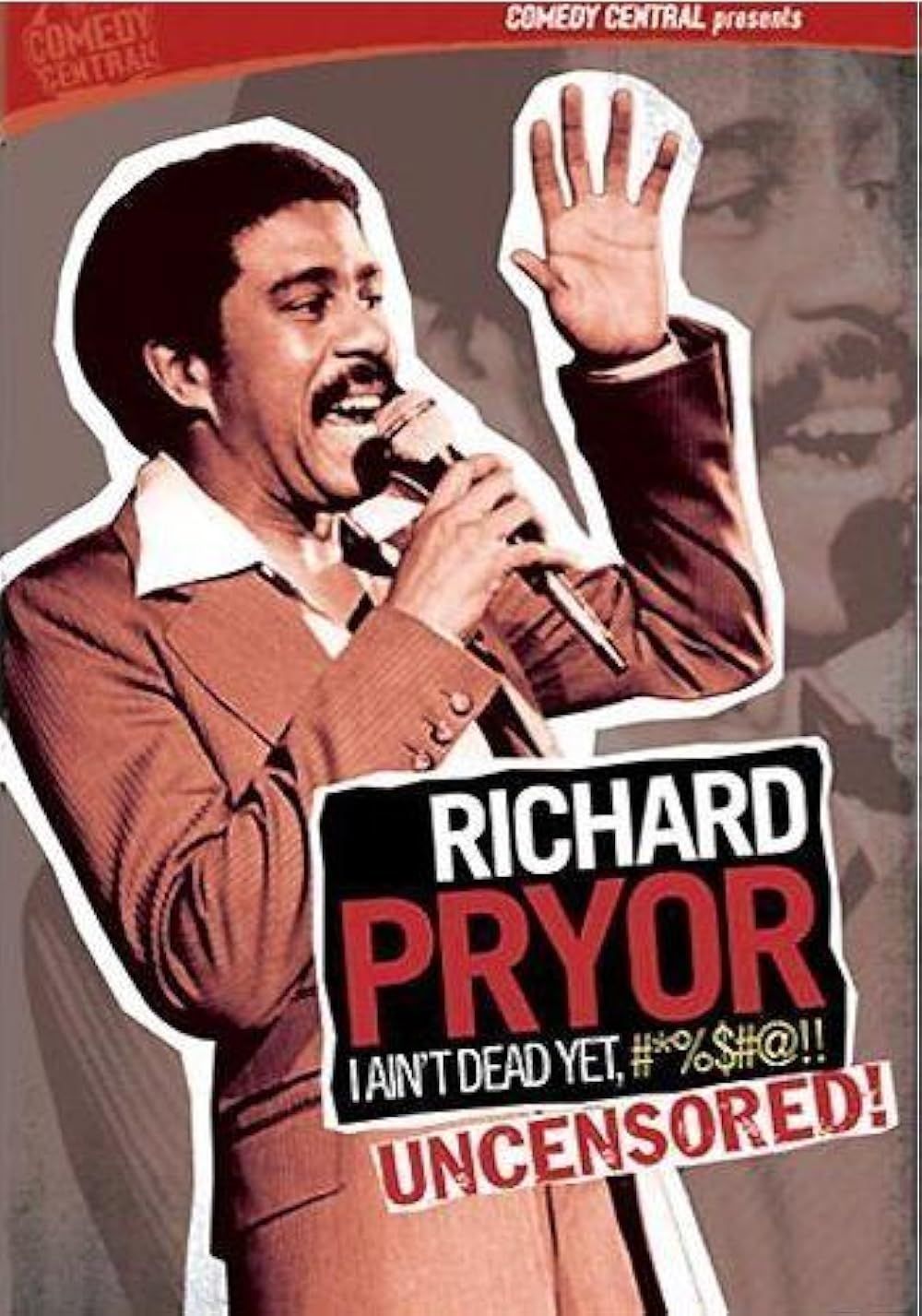

When Pryor’s last special, I Ain’t Dead Yet, #%$#@!!*, was announced in 2003, I felt a mix of emotions. I was excited to watch a genius at work again but terrified of what MS might have done to him. I was two years into my own diagnosis, still pretending at work that my vertigo was just a concussion. I wanted to laugh, but I also wanted to know had the disease stolen his gift? Would it steal mine?

Around that time, A Current Affair rebroadcasted an old 1996 interview with Pryor. At the end, the reporter asked if they could play a word association game, just like the SNL skit that had made him famous. Pryor agreed, and they went back and forth. Then came the word multiple sclerosis

I smiled, already knowing his answer. Mother@#$_!! It was his favorite word, and it was exactly how I felt about the disease.

But Pryor didn’t curse. His eyes welled up, and he simply said, “Gift.”

I didn’t understand. A gift? MS had destroyed his body, taken his career, stolen his voice. How the hell was this a gift?

Years passed. I went on short-term disability multiple times, dealing with gait and vision issues, not to mention pain. I lost my career. Long-term disability followed, and I became visibly disabled.

Gift?

I kept coming back to that word. I wanted to feel what Pryor had felt, to reach some enlightened state where I saw my illness as a blessing. But I couldn’t. I was angry. I was bitter.

Still, time has a way of forcing perspective. In my forties now, after 16 years of reflection, I can finally see the other side of things.

MS has given me something. It forced me to be present. It made me cherish every moment I have with my wife and kids. I was home for all three of my wife’s maternity leaves. I was there for the preschool years, the first steps, the little moments most fathers miss.

But would I call it a gift? No. If I could erase it, I would. I won’t pretend otherwise.

Maybe Pryor had reached a level of peace I never will. Or maybe, at the end of that interview, he was just trying to convince himself.

Leave a Reply